Some notes on Models of Environments

Suppose you are given a dataset on some process with the following attributes. The process that generates the data is complex and not fully observable. The data only captures part of dynamics of the process. Part of the dynamics involve decisions that you can control at some point in the future. The hope is that these knobs will be determined by some suitably advanced intelligence that needs to be determined as well. So you have two problems, (a) from the dataset infer process dynamics in a reasonable manner, and (b) determine an optimal policy that can control the environment determined in (a).

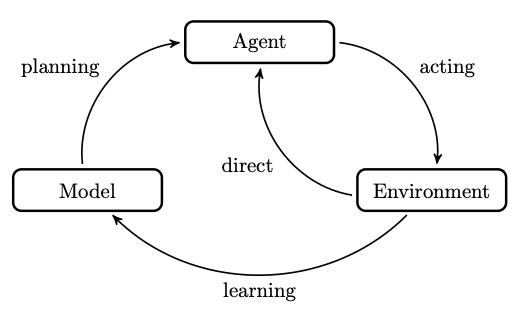

In established reinforcement learning parlance, the first problem deals with specifying the environment, and the second deals with defining the agent. This post is a short discussion of the former.

What is an environment anyway?

The environment is the model of the world that the agent interacts with. It is associated with variables that describe its state. For instance, in an environment describing an HVAC system, one of the state variables could be the temperature of the room. If an agent acts on this state, then the environment must minimally provide the next state and an estimate of the reward. We’ll get to the reward shortly. An agent in our HVAC example could be a person changing the temperature control. As a result of that change, the environment then provides a revised temperature of the room for the next time step.

The reward is a numeric value that encodes desirable behaviour that an agent seeks. In the HVAC example, this could be the negative of the absolute temperature difference between a desired temperature and the actual temperature (in the state variable). This way, when we maximise reward, we aim to keep the temperature close to the desired one (without getting too hot or too cold).

Therefore the environment must be able to assess the impact of an agent action on its state. In other words, it must encode transition dynamics in some way. Additionally, it must estimate reward for a specific action when at a specific state. If you have these two elements, i.e. transitions and rewards, explicitly then you effectively have yourself a model of the environment!

Modeling this explicitly is not necessary for reinforcement learning. You can short cut the model by directly interacting with the environment. This is known as the model-free approach. These approaches do not make any assumptions beyond having a reward signal. So coming back to your problem at hand, you broadly have two choices:

- experience-based/model-free: where you just sample next-state and reward based on past experiences that were similar (without bothering to actually learning anything about the process),

- model-based: where you explicitly try to learn elements of the underlying process (both transitions and rewards).

This distinction seems to be emphasized in the literature more than what the definitions suggest. The principle difference being where the transitions come from. So which path do you choose for the problem?

As always, it depends! When you have a model of the environment, its easier to gather data (you can simply generate more), but may be harder to learn the policy itself and require additional assumptions. A model may allow for appropriate abstraction of complexity from the real environment. On the other hand, model-free methods may be effective for complex policies, but require a lot of experience (i.e. slower), and generally not transferable across tasks.

Let’s build a model of the environment

Assume for the task at hand, the model-based approach is attractive. You have sufficient data to supervise the learning of transition and reward functions. You still have some choices on how to proceed.

The Deep Mind Lecture on this topic has a nice overview of the main methods for model learning. Formally, our data represents a state-action-reward trajectory sequence, i.e. $$(S_1, A_1, R_1, S_2, …, S_t, A_t, R_t, …)$$, which is our experience. From this experience, we try to learn what the likely transitions and rewards are. To do so, we treat this as a supervised problem, i.e. $(S_1, A_1) \rightarrow (R_2, S_2)$, and in general $(S_{t}, A_t) \rightarrow (R_{t+1}, S_{t+1})$.

We then choose a function $f$, that given a state and action will provide the next state and reward, i.e. $$f(s, a) = r, s^\prime$$. We learn any parameters associated with $f$ by minimising a chosen loss function. The result is an expectation model. There are some issues with expectation models for discrete values, but for linear values of you are mostly fine.

For some cases the outcomes may not be deterministic or you may need to predict exact viable states. In this case, a stochastic model (or a generative model) provides a sample of the next likely state but introduces noise in the process of doing so. For cases where the state and action spaces are not prohibitively large, a full model can be determined.

Its also useful to distinguish between off-policy and on-policy methods at this point. An off-policy algorithm uses trajectories generates by some other policy to learn better policies for the agent. Examples of off-policy methods include Q-learning. On-policy algorithms on the other hand train an agent and use the same policy as its being learnt. Examples include SARSA.